In the introduction to the book, Modern Mothers in the Heartland, a speech by Dr. Caroline Hedger is referenced. In 1920 Dr. Caroline Hedger gave a speech entitled, “The Relation of Health to Progress”. Like reformers of the time she was calling attention to the health of women and children.

A broad coalition of public health practitioners, social welfare advocates, and women’s rights supporters argued that a sound and democratic future depended upon mothers’ ability to produce and maintain a robust citizenry.1

It seems to me that this is still a valid concern.

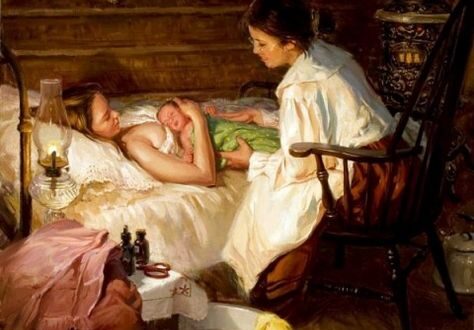

In an autobiography, Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen wrote about her experience as an obstetrician.

Midwifery exacts a toll of the mental, physical, and emotional reserves of the physician that is comparable to no other specialty, and for this reason, in solving the problem of obstetrical anesthesia, the obstetrician should be considered along with the expectant mother and baby. For fifteen years after I began practice I delivered patients in their homes, and regardless of assistance it was I, the doctor, upon whom the morale of the patient and family rested. I was called when labor was evident, and I never left my patient until she had been delivered . . . Hospitalization of the obstetric patient decreases the time and inconvenience of the physician by seventy-five percent.2

Dr. Van Hoosen was a proponent of twilight sleep and devised methods to keep disoriented and combative patients in their beds: adult cribs, a patient gown that had one long sleeve that trapped both arms and delivery tables with restraints.

When I began working as a labor nurse at a hospital in Detroit twilight sleep was being phased out, but the labor room still had beds with high side rails that were like those of a crib. Delivery tables still had wrist restraints as well as stirrups with restraints for legs.

These female physicians in the early 1900s worked hard for women and children’s health. Yet, it is unfortunate that trained midwives were sidelined at this time. Midwives and doctors had different skills and perspectives; they could have benefited from working together. As the medical profession grew the gap between midwives and doctors expanded.

I subscribe to Midwifery Today. The summer issue has an article titled, “The Way of Birth”. The author wrote: My friend and assistant midwife in the 1970s, Deni and I would walk the concrete paths of Kansas City, Missouri, and point out who was under the care of a board-certified obstetrician . . . We predicted then what we are living today: that few babies would be born “under the stars”. We predicted that we would see conception become a medical procedure not unlike what we watched happen to birth. That the body of a woman and the making, growing, birthing, and feeding of a baby would be delivered into the hands of medicine and machines. And men. 3

My recent mail included a publication, Panacea, from the University of Michigan School of Nursing. I was pleased to see an article4about the accomplishment of midwives in Liberia. Inspired by midwife Jody Lori, Maternity Waiting Homes have been established in Liberia in an effort to reduce maternal and infant deaths. Expectant mothers come to the homes, which are located close to health clinics, in the last few weeks of pregnancy.

It is my hope that the midwife model of birth would gain greater respect in the United States. Have you given birth? What was your experience like?

If you enjoyed this post I hope you subscribe to my blog and visit my facebook page.

1Curry, Lynne, Modern Mothers in the Heartland: Gender Health, and Progress in Illinois, 1900 – 1930, Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1999, p.1

2Van Hoosen, Bertha, Petticoat Surgeon, New York: Pellegrini & Cudahy Publishers, 1947, p. 272 -273.

3Sister Morning Star, “The Way of Birth”, Midwifery Today, Summer 2018, Issue 126, p. 21

4Meyers, Jaime, “The Road to Maternal Health”, Panacea, School of Nursing University of Michigan, summer 2018, p. 8-11